The Golden Age: A Novel

The Golden Age: A Novel Death Before Bedtime

Death Before Bedtime Burr

Burr The Last Empire

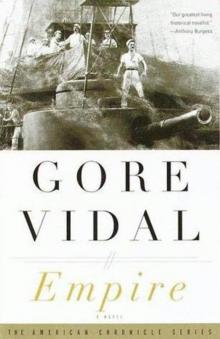

The Last Empire Empire: A Novel

Empire: A Novel The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal

The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal Live From Golgotha

Live From Golgotha Lincoln

Lincoln Death Likes It Hot

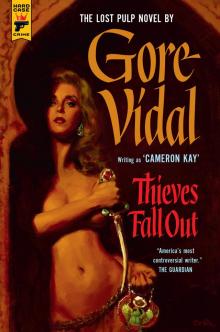

Death Likes It Hot Thieves Fall Out (Hard Case Crime)

Thieves Fall Out (Hard Case Crime) Point to Point Navigation

Point to Point Navigation Williwaw

Williwaw Death in the Fifth Position

Death in the Fifth Position In a Yellow Wood

In a Yellow Wood Julian

Julian Hollywood

Hollywood Myra Breckinridge

Myra Breckinridge Messiah

Messiah The Second American Revolution and Other Essays 1976--1982

The Second American Revolution and Other Essays 1976--1982 Homage to Daniel Shays

Homage to Daniel Shays Empire

Empire Thieves Fall Out

Thieves Fall Out 1876

1876 The City and the Pillar

The City and the Pillar The Golden Age

The Golden Age At Home

At Home