- Home

- Gore Vidal

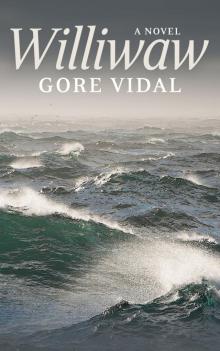

Williwaw

Williwaw Read online

© Burtyrki Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publisher’s Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Author’s original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern reader’s benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

WILLIWAW

A Novel By

GORE VIDAL

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS 4

DEDICATION 5

Chapter One 6

i 6

ii 17

iii 21

Chapter Two 26

i 26

ii 33

iii 40

Chapter Three 45

i 45

ii 50

iii 56

Chapter Four 64

i 64

ii 69

iii 74

Chapter Five 81

i 81

ii 85

iii 94

Chapter Six 100

i 100

ii 104

iii 113

Chapter Seven 118

i 118

ii 122

iii 132

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER 138

DEDICATION

* * *

For Nina

* * *

NOTE: Williwaw is the Indian word for a big wind peculiar to the Aleutian islands and the Alaskan coast. It is a strong wind that sweeps suddenly down from the mountains toward the sea. The word williwaw, however, is now generally used to describe any big and sudden wind. It is in this last and more colloquial sense that I have used the term.

G. V.

* * *

All of the characters, all of the events and most of the places in this book are fictitious.

Chapter One

i

SOMEONE turned on the radio in the wheelhouse. A loud and sentimental song awakened him. He lay there for a moment in his bunk and stared at the square window in the wall opposite him. A sea gull flew lazily by the window. He watched it glide back and forth until it was out of sight.

He yawned and became conscious of an ache behind his eyes. There had been a party, he remembered. He felt sick. The radio became louder as the door to his cabin opened. A brown Indian face looked in at him.

“Hey, Skipper, chow’s ready below.” The face vanished.

Slowly he got out of his bunk and onto the deck. He stood in front of the mirror. Cautiously he pressed his fingers against his eyelids and morbidly enjoyed the pain it gave him. He noticed his eyes were bloodshot and his face was grimy. He scowled at himself in the mirror. From the wheelhouse the sound of Negro music thudded painfully in his ears.

“Turn that damn thing off!” he shouted.

“O.K., Skipper,” his second mate’s voice answered. The music faded away and he began to dress. The second mate came into the cabin. “Quite a party, wasn’t it, Mr. Evans?”

Evans grunted. “Some party. What time is it?”

The mate looked at his watch. “Six-twenty.”

Evans closed his eyes and began to count to himself: one, two—he had had four hours and thirty minutes of sleep. That was too little sleep. The mate was watching him. “You don’t look so good,” he said finally.

“I know it.” He picked up his tie. “Anything new? Weather look all right?”

The mate sat down on the bunk and ran his hands through his hair. It was an irritating habit. His hair was long and the color of mouldering straw; when he relaxed he fingered it. On board a ship one noticed such things.

“Weather looks fine. A little wind from the south but not enough to hurt. We scraped some paint off the bow last night. I guess we were too close to that piling.” He pushed back his hair and left it alone. Evans was glad of that.

“We’ll have to paint the whole ship this month anyway.” Evans buttoned the pockets of his olive-drab shirt. High-ranking officers were apt to criticize, even in the Aleutians. He pinned the Warrant Officer insignia on his collar. His hands shook.

Bervick watched him. “You really had some party, I guess.”

“That’s right. Joe’s going back to the States on rotation. We were celebrating. It was some party all right.” Evans rubbed his eyes. “Have you had chow yet, Bervick?”

The mate, Bervick, nodded. “I had it with the cooks. I’ve been around since five.” He stood up. He was shorter than Evans and Evans was not tall. Bervick was lightly built; he had large gray Norwegian eyes, and there were many fine lines about his eyes. He was an old seaman at thirty.

“I think I’ll go below now,” said Evans. He stepped out of his cabin and into the wheelhouse, glancing automatically at the barometer. The needle pointed between Fair and Change; this was usual. He went below. At the end of the companionway, the doors to the engine room were open and the generator was going. The twin Diesel engines were silent. He went into the galley.

John Smith, the Indian cook, was kneading dough. He was a bad cook from southeastern Alaska. Cooks of any kind were scarce, though, and Evans was glad to have even this bad one.

“What’s new?” asked Evans, preparing to listen to Smitty’s many troubles.

“The new cook.” Smitty pointed to a fat man in a white apron gathering dishes in the dining salon.

“What’s wrong now?”

“I ask him to wash dishes last night. It was his turn, but he won’t do nothing like that. So I tell him what I think. I tell him off good, but he no listen. I seen everything now...Smitty’s black eyes glittered as he talked. Evans stopped him.

“O.K. I’ll talk to him.” He went into the dining salon. Here two tables ran parallel to the bulkheads. One table was for the crew; the other for the ship’s officers and the engineers. The crew’s table was empty; only the Chief Engineer, Duval, sat at the other table.

“Morning, Skipper,” he said. He was an older man. His hair was gray and black in streaks. It was clipped very short. His nose was long and hooked and his mouth was wide but not pleasant. Duval was a New Orleans Frenchman.

“Good morning, Chief. Looks like everybody’s up early today.”

“Yeah, I guess they are at that.” The Chief cleared his throat. He waited for a comment. There was none. Then he remarked casually, “I guess it’s because they all heard we was going to Arunga. I guess that’s just a rumor.” He looked at his fork. Evans could see that he was anxious to know if they were leaving. The Chief would never ask a direct question, though.

The fat cook put a plate of eggs in front of Evans and poured him some black coffee. The cook’s hand was unsteady and the coffee spilled on the table. The cook ignored the puddle of coffee, and went back into the galley.

Evans watched the brown liquid drip slowly off onto the deck. Dreamily he made patterns with his forefinger. He thought of Arunga island. Finally he said, “I wonder where they pick up rumors like that?”

“Just about anywhere,” said the Chief. “They probably figured we was going there because that’s our port’s headquarters and the General’s Adjutant is here and they say he’s breaking his back to get back fast and that there aren’t no planes flying out for a week. We’re the only ship in the harbor that could take him to Arunga.”

“That sounds pretty interesting,” said Evans and he began to eat. Duval scowled and pushed back his chair from the table. He s

tood up and stretched himself. “Arunga’s a nice trip anyway.” He waited for a remark. Again there was none. “Think I’ll go look at the engines.”

Evans smiled as he left. Duval did not think highly of him. Evans was easily half the Chief Engineers age and that meant trouble. The Chief thought that age was a substitute for both brains and experience; Evans could not like that idea. He knew, however, that he would eventually have to tell the Chief that they were leaving for Arunga.

Evans ate quickly. He noticed that the first mate’s place was untouched. He would have to speak to him again about getting up earlier.

Breakfast over, he left the salon by the after door. He stood on the stern and breathed deeply. The sky was gray. A filmy haze hung over the harbor and there was no wind. The water of the harbor was like a dark glass. Overhead the sea gulls darted about, looking for scraps on the water. A quiet day for winter in these islands.

Evans climbed over the starboard side and stepped down on the dock. There were two large warehouses on the dock. They were military and impermanent. Several power barges were moored near his ship and he would have to let his bow swing far out when they left; mechanically, he figured time and distance.

Longshoremen in soiled blue coveralls were loading the barges, and the various crews, civilians and soldiers mixed, were preparing to cast off for their day’s work in the harbor.

A large wooden-faced Indian skipper shouted at Evans from the wheelhouse of one of the barges. Evans shouted back a jovial curse; then he turned and walked across the dock to the shore.

Andrefski Bay was the main harbor for this Aleutian island. The bay was well protected, and, though not large, there were no reefs or shallow places in the main part of the harbor. No trees grew on the island. The only vegetation was a coarse brown turf which furred the low hills that edged the bay. Beyond these low hills were high, sharp and pyramidal mountains, blotched with snow.

Evans looked at the mountains but did not see them. He had seen them many times before and they were of no interest to him now. He never noticed them. He thought of the trip to Arunga. A good trip to make, a long one, three days, that was the best thing about going. He had found that when they were too much in port everyone got a little bored and irritable. A change would be good now.

Someone called his name. He looked behind him. The second mate, Bervick, was hurrying toward him.

“Going over to the office, Skipper?” he asked, when he had caught up.

“That’s right. Going to pick up our orders.”

“Arunga?”

“Yes.” They walked on together.

The second mate was not wearing his Technical Sergeant’s stripes. Evans hoped the Adjutant would not mind. One could never tell about these Headquarters people. He would warn Bervick later.

They walked slowly along the black volcanic ash roadway. At various intervals there were wooden huts and warehouses. Between many of the buildings equipment was piled, waiting to be shipped out.

“It’s been almost a year since we was to Arunga,” remarked Bervick.

“That’s right.”

“Have we got some new charts?”

“We got them last fall, remember?”

“I guess I forgot.” A large truck went by them and they stood in the shallow gutter until it had passed.

“You seen the sheep woman lately?” asked Evans.

The sheep woman was the only woman on the island. She was a Canadian who helped run the sheep ranch in the interior. She had been on the island for several years, and, though middle-aged, stout, and reasonably virtuous, the rumors about her were damning. It was said that she charged fifty dollars for her services and everyone thought that that was too much.

Bervick shook his head. “I don’t know how she’s doing. O.K., I suppose. I’m saving up for when we hit the Big Harbor next. I don’t want nothing to do with her.”

Evans was interested. Who’ve you got in mind at Big Harbor?”

“I thought she was the Chief’s property.”

Bervick shrugged. “That’s what he says. She’s a good girl.”

“I suppose so.”

“I like her. The Chief’s just blowing.”

“None of them are worth much trouble.”

A light rain began to fall. The office was still a half a mile ahead of them. All the buildings of the port were, for the sake of protection, far apart.

“Damn it,” muttered Evans, as the rain splattered in his face. A truck came up behind them. It stopped and they climbed into the back. Evans told the driver where they were going, then he turned to Bervick. “You better pick up the weather forecast today.”

“I will. I think it’ll be pretty good.”

“Hard to say. This is funny weather.”

The truck let them off at the Army Transport Service Office. The office was housed in a long, one-storied, gray building.

The outer room was large, and here four or five enlisted men were doing clerical work beneath fluorescent lights. The walls were decorated with posters warning against poison gas, faulty camouflage, and venereal disease.

One of the clerks spoke to Evans. “The Captain’s waiting for you,” he said.

“I think I’ll go check with Weather,” said Bervick. “I’ll see you back to the boat.”

“Fine.” Evans walked down a corridor to the Captain’s office.

A desk and three neat uncomfortable chairs furnished the room. On the walls were pictures of the President, several Generals, and several nudes. The nudes usually came down during inspections.

The Captain was sitting hunched over his desk. He was a heavy man with large features. He was smoking a pipe and talking at the same time to a Major who sat in one of the three uncomfortable chairs. They looked up as Evans entered.

“Hello there, Skipper,” said the Captain and he took his pipe out of his mouth. “I want you to meet an old friend of mine, Major Barkison.”

The Major stood up and shook hands with Evans. “Glad to know you, Mister...”

“Evans.”

“Mister Evans. It looks as if you’ll be pressed into service.”

“Yes it does...sir.” He added the “sir” just in case.

“I hope the trip will be a calm one,” remarked the Major with a smile.

“It should be.” Evans relaxed. The Major seemed to be human.

Major Barkison was a West Pointer and quietly proud of the fact. Though not much over thirty he was already bald. He had a Roman nose, pale blue eyes, and a firm but small chin. He looked like the Duke of Wellington. Knowing this, he hoped that someone might someday mention the resemblance; no one ever did, though.

“Sit down here, Evans,” said the Captain, pointing to one of the chairs. The Major and Evans both sat down. “We’re sending you out on a little trip to Arunga. Out west where the deer and submarines play.” He laughed heartily at his joke. Evans also laughed. The Major did not.

The Major said, “How long will the trip take you?”

“That’s hard to say.” Evans figured for a moment in his head. “Seventy hours is about average. We can’t tell until we know the weather.”

Barkison nodded and said nothing.

The Captain blew a smoke ring and watched it float ceilingward, his little eyes almost shut. “The weather reports are liable to be pretty lousy,” he said at last.

Barkison nodded again. “Yes, that’s right. That’s why I can’t fly out of here for at least a week. Everything’s grounded. That’s why I can’t get out of here. It is imperative that I get back to Headquarters.”

“The war would stop if you didn’t get back, wouldn’t it, Major?” The Captain said this jovially but Evans thought there was malice in what he said.

“What do you mean, Captain?” said the Major stiffly.

“Nothing at all, sir. I was just joking. A bad habit of ours here.” Evans smiled to himself. He knew that the Captain did not like regular army men. The Captain had been in the grain business and he was proud that

he made more money than the men in the regular army. They did not understand business and the Captain did. This made a difference. The Major frowned.

“I have to get my reports in, you know. You understand that, of course. You know I would never have a boat sent out in weather like this unless it were important. This weather precludes air travel,” he added somewhat pompously, enjoying the word “preclude.” It had an official sound.

“Certainly, Major.” The Captain turned to Evans. “From what I gather the trip shouldn’t be too bad, a little rough perhaps, but then it usually is. You had better put into the Big Harbor tomorrow and get a weather briefing there. I got some cargo for them, too. I told the boys to load you up today.” He paused to chew on his pipe. “By the way,” he said in a different voice, “how do you feel after our little party last night?”

Evans grimaced. “Not very good. The stuff tasted like raisin jack.”

“You should know.” The Captain laughed loudly and winked. Barkison looked pained. He cleared his throat.

“I guess you people have a hard time getting liquor up here.” He tried to sound like one of the boys and failed.

“We manage.” The Captain chuckled.

The door opened. A young and pink-faced Lieutenant looked doubtfully about the room until he saw the Major.

“Come in, Lieutenant,” said the Major.

“Lieutenant Hodges, this is Mr. Evans.” The two shook hands and sat down. The young Lieutenant was very solemn.

“Is there anything new on our leaving, sir?” he asked.

“Yes,” said Barkison. “Weather permitting, we’ll leave tomorrow morning. We should be back...how long did you say?”

“Maybe three days, maybe less,” Evans answered.

“Isn’t that awfully long, sir? I mean we have to be back day after tomorrow.”

The Major shrugged. “Nothing we can do about it. There are no planes going out for an indefinite period.”

“Well,” the Captain stood up and Evans did the same, “you had better check on the weather and take water and do whatever else you have to do. You’ll definitely leave tomorrow morning and you’ll stop off at the Big Harbor. See you later today.” He turned to the Major. “If you’d like to move aboard tonight....”

The Golden Age: A Novel

The Golden Age: A Novel Death Before Bedtime

Death Before Bedtime Burr

Burr The Last Empire

The Last Empire Empire: A Novel

Empire: A Novel The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal

The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal Live From Golgotha

Live From Golgotha Lincoln

Lincoln Death Likes It Hot

Death Likes It Hot Thieves Fall Out (Hard Case Crime)

Thieves Fall Out (Hard Case Crime) Point to Point Navigation

Point to Point Navigation Williwaw

Williwaw Death in the Fifth Position

Death in the Fifth Position In a Yellow Wood

In a Yellow Wood Julian

Julian Hollywood

Hollywood Myra Breckinridge

Myra Breckinridge Messiah

Messiah The Second American Revolution and Other Essays 1976--1982

The Second American Revolution and Other Essays 1976--1982 Homage to Daniel Shays

Homage to Daniel Shays Empire

Empire Thieves Fall Out

Thieves Fall Out 1876

1876 The City and the Pillar

The City and the Pillar The Golden Age

The Golden Age At Home

At Home