- Home

- Gore Vidal

1876

1876 Read online

ACCLAIM FOR

GORE VIDAL’s

1876

“A glorious piece of writing….Vidal’s words turn each page into a tray of jewelry.”

—Harper’s

“Superb….Simply splendid….A thoroughly grand book—must, must reading for everyone.”

—Business Week

“Crackles with life—high and low….Renders the sights and sounds of New York City a century ago unforgettable.”

—New York Sunday News

“Clearly one of Vidal’s brightest works.”

—The Plain Dealer

GORE VIDAL

1876

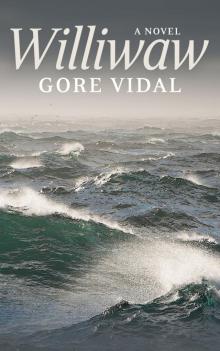

Gore Vidal was born in 1925 at the United States Military Academy at West Point. His first novel, Williwaw, written when he was nineteen years old and serving in the Army, appeared in the spring of 1946. He subsequently wrote twenty-three novels, five plays, many screenplays, short stories, well over two hundred essays, and two memoirs. He died in 2012.

NARRATIVES OF EMPIRE

BY

GORE VIDAL

Burr

Lincoln

1876

Empire

Hollywood

Washington, D.C.

The Golden Age

FIRST VINTAGE INTERNATIONAL EDITION, FEBRUARY 2000

Copyright © 1976 by Gore Vidal

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, in 1976.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage International and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Random House edition as follows: Vidal, Gore, 1925–

1876: a novel.

1. United States—History—1865-1898—Fiction. I. Title.

PZ3.V6668Ei [PS3543.I26] 813’.5’4 75-34311

ISBN 0-394-49750-3 Trade Hardcover

Vintage ISBN 9780375708725

Ebook ISBN 9780525565772

www.vintagebooks.com

v5.3.2

a

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Also by Gore Vidal

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Afterword

For Claire Bloom

One

1

“THAT IS NEW YORK.” I pointed to the waterfront just ahead as if the city were mine. Ships, barges, ferry boats, four-masted schooners were shoved like a child’s toys against a confused jumble of buildings quite unfamiliar to me, a mingling of red brick and brownstone, of painted wood and dull granite, of church towers that I had never seen before and odd bulbous-domed creations of—cement? More suitable for the adornment of the Golden Horn than for my native city.

“At least I think it is New York. Perhaps it is Brooklyn. I am told that the new Brooklyn is marvellously exotic, with a thousand churches.”

Gulls swooped and howled in our wake as the stewards on a lower deck threw overboard the remains of the large breakfast fed us at dawn.

“No,” said Emma. “I’ve just left the captain. This is really New York. And how old, how very old it looks!” Emma’s excitement gave me pleasure. Of late neither of us has had much to delight in, but now she looks a girl again, her dark eyes brilliant with that all-absorbed, grave, questioning look which all her life has meant: I must know what this new thing is and how best to use it. She responds to novelty and utility rather than to beauty. I am the opposite; thus father and daughter balance each other.

Grey clouds alternated with bands of bright blue sky; sharp wind from the northwest; sun directly in our eyes, which meant that we were facing due east from the North River, and so this was indeed the island of my birth and not Brooklyn to the south nor Jersey City at our back.

I took a deep breath of sea-salt air; smelt the city’s fumes of burning anthracite mingled with the smell of fish not lately caught and lying like silver ingots in a passing barge.

“So old?” I had just realized what Emma had said.

“But yes.” Emma’s English is almost without accent, but occasionally she translates directly from the French, betraying her foreignness. But then I am the foreign one, the American who has lived most of his life in Europe while Emma has never until now left that old world where she was born thirty-five years ago in Italy, during a cyclone that uprooted half the trees in the garden of our villa and caused the frightened midwife nearly to strangle the newborn with the umbilical cord. Whenever I see trees falling before the wind, hear thunder, observe the sea furious, I think of that December day and the paleness of the mother’s face in vivid contrast to the redness of her blood, that endless haemorrhaging of blood.

(I think that a little mémoire in the beautiful lyric style of the above might do very well for the Atlantic Monthly.)

Emma shivered in the wind. “Yes, old. Dingy. Like Liverpool.”

“Waterfronts are the same everywhere. But there’s nothing old here. I recognize nothing. Not even City Hall, which ought to be over there where that marble tomb is. See? With all the columns…”

“Perhaps you’ve forgotten. It’s been so long.”

“I feel like Rip Van Winkle.” Already I could see the beginning of my first piece for the New York Herald (unless I can interest Mr. Bonner at the New York Ledger; he has been known to pay a thousand dollars for a single piece). “The New Rip Van Winkle, or How Charles Schermerhorn Schuyler Sailed to Europe Almost Half a Century Ago…” And stayed there (asleep?). Now he’s come home, to report to President Martin Van Buren who sent him abroad on a diplomatic mission, to compare foreign notes with his friend Washington Irving (who invented him after all), to dine with the poet Fitz-Greene Halleck: only to find all of them, to his astonishment, long dead.

Must stop at this point.

These pages are to be a quarry, no more. A collection of day-to-day impressions of my new old country.

Titles: “The United States in the Year of the Centennial.”

“Traveller’s Return.” “Old New York: A Knickerbocker’s Memories.” “Recollections of the Age of Jackson and Van Buren…” Must try these out on publishers and lecture agents.

* * *

—

At this moment—midnight, December 4, 1875—I am somewhat staggered at the prospect of trying in some way to encompass with words this new world until now known to me only at the farthest remove. I can of course go on and on about the past, write to order of old things by the yard; and happily there is, according to my publisher, Mr. E. P. Dutton, a considerable market for my wares whenever I am in the reminiscent mood. But the real challenge, of course, is to get the sense of the country as it is today—two, three, four times more populous than it was when I left in 1837. Yet, contemplating what I saw of New York this afternoon, I begin only now to get the range as I sit, pe

rspiring, in the parlour of our hotel suite while dry heated air comes through metal pipes in sudden blasts like an African sirocco.

None of the Americans I have met in Europe over the past four decades saw fit to prepare me for the opulence, the grandeur, the vulgarity, the poverty, the elegance, the awful crowded abundance of this city, which, when I last saw it, was a minor seaport with such small pretensions that a mansion was a house like Madame Jumel’s property on the Haarlem—no, Harlem—no, Washington Heights—a building that might just fill the ballroom of one of those palaces the rich are building on what is called Fifth Avenue, in my day a country road wandering through the farms north of Potter’s Field, later to be known as the Parade Ground, and later still as Washington Square Park, now lined with rows of “old” houses containing the heirs of the New York gentry of my youth.

In those days, of course, the burghers lived at the south end of the island between the Battery and Broadway where now all is commercial, or worse. I can recall when St. Mark’s Place was as far north as anyone would want to live. Now, I am told, a rich woman has built herself a cream-coloured French palace on Fifty-seventh Street! opposite the newly completed Central Park (how does one “complete” a park?).

A steward hurried across the deck to Emma. “C’est un monsieur; il est arrivé, pour Madame la Princesse.”

Everyone told us that of all the Atlantic ships those of the French line were the most comfortable, and so the Pereire proved to be, despite winter gales that lasted from Le Havre to the mid-Atlantic. But the captain was charming; and most impressed by Emma’s exalted rank even though her title is Napoleonic and the second French empire is now the third French republic. Nevertheless, the captain gave us a most regal series of staterooms for only a hundred and fifty dollars (the usual cost of two first-class passages is two hundred dollars).

Our fellow passengers proved to be so comfortably dull that I was able during the eight and a half days of the crossing to complete my article for Harper’s Monthly, “The Empress Eugénie in Exile,” filled with facts provided by the Emperor’s cousin, my beloved Princess Mathilde who of course detests her. Conforming to current American taste, the tone of the piece is ecstatic and somewhat fraudulent.

But the Empress has always been most kind to Emma and to me, although she once tactlessly said in my presence that literary men give her the same sense of ennui as explorers! Well, the writer is not unlike the explorer. We, too, are searching for lost cities, rare tigers, the sentence never before written.

Emma’s visitor was John Day Apgar. We found him in the main salon. Rather forlornly, he stood amongst the crowd of first-class passengers, all looking for children, maids, valets, trunks.

Quite a number of the men were having what the Americans so colorfully refer to as “an eye-opener” at the marble-topped bar.

“Princess!” Mr. Apgar bowed low over Emma’s hand; his style is not bad for an American. But then John, as I call him, was for a year at our embassy in Paris. Now he is practising law in New York.

“Mr. Apgar. You are as good as your word.” Emma gave him her direct dark gaze, not quite as intense as the one she gave New York City, but then John, unlike the city, is a reasonably well known and familiar object to her. “I’ve a carriage waiting for you at Pier Fifty. Porters—everything. Forgive me, Mr. Schuyler.” John bowed to me; shook hands.

“How did you get on board?” I was curious. “Aren’t we still in the harbour?”

“I came out on the tender. With all sorts of people who have come to greet you.”

“Me?” I was genuinely surprised. I had telegraphed Jamie Bennett at the Herald that I was arriving on the fourth but I could hardly expect that indolent youth to pay me a dawn visit in the middle of the Hudson River. Who else knew of my arrival?

The captain enlightened us. “The American newspaper press is arrived on board to interview Monsieur Schuyler.” The French pronunciation of Schuyler (Shwee-lair) is something I shall never grow used to or accept. Because of it, I feel an entirely different person in France from what I am in America. Question: Am I different? Words, after all, define us.

“How extraordinary!” Emma takes a low view of journalists despite the fact that my livelihood from now on must come from my pen, from writing for newspapers, magazines, anything and everything. The panic of 1873 wiped out my capital, such as it was. Worse, Emma’s husband left her in a similar situation when he saw fit to die five years ago while ingesting a tournedos Rossini at the restaurant Lucas Carton.

Whether it was a heart attack or simply beef with foie gras lodged in the windpipe, we shall never know, since neither of us was present when the Prince d’Agrigente so abruptly departed this world during a late supper with his mistress. It was the scandal of Paris during the three days before the war with Prussia broke out. After that, Paris had other things to talk about. We did not. To this day none of us understands how it was that the Prince died owing the fortune that we thought he had possessed.

With the slightly shady pomp of a chamberlain at the imperial court, the captain led us across the salon to a small parlor filled with gilt chairs à la Louis Quinze where, waiting for me, was the flower of the youth of the New York press. That is to say, the new inexperienced journalists who are assigned to meet celebrities aboard ships in the harbour and, through trial and error (usually more of the second than of the first), learn the art of interviewing, of misdescribing in sprightly language odd fauna.

Twenty, thirty faces stared at me from a variety of long shabby overcoats, some open in response to the warmth of the cabin, others still tightly shut against the morning’s icy wind. We have been told a hundred times today that this has been the coldest winter in memory. What winter is not?

The captain introduced me to the journalists—obviously he is well-pleased that the reduction in our fare has been so dramatically and immediately justified. I sang for all our suppers; spoke glowingly of the splendour of the French line.

Questions were hurled at me whilst a near-sighted artist scribbled a drawing of me. I caught a glimpse of one of his renderings when he flipped back the first page of his paper block: a short stout pigeon of a man with three chins lodged in an exaggerated high-winged collar (yet mine is what collars should be), and of course the snubbed nose, square jaw of a Dutchman no longer young. Dear God! Why euphemize? Of a man of sixty-two, grown very old.

Thin man from the New York Herald. Indolent youth from the New York Graphic. Sombre dwarf from The New York Times. The Sun, Mail, World, Evening Post, Tribune were also present but not immediately identified. Also half a dozen youths from the weeklies, the monthlies, the biweeklies, the bimonthlies…oh, New York, the United States is the Valhalla of journalism—if Valhalla is the right word. Certainly, there are more prosperous newspapers and periodicals in the United States than in all of Europe put together. As a result, today’s men of letters come from the world of journalism, and never entirely leave it—unlike my generation, who turned with great reluctance to journalism in order to make a desperate, poor living of the sort that now faces me.

“What, Mr. Schuyler, are your impressions of the United States today?” The dwarf from The New York Times held his notebook before him like a missal—studying it, not me.

“I shall know better when I go ashore.” Pleased chuckles from the overcoats that had begun to give off a curious musty odour of dirty wool dampened by salt spray.

Handkerchief to face, Emma stood at the door, ready for flight. But John Apgar appeared to be entirely fascinated by the Fourth Estate in all its woolly splendour.

“How long has it been, sir, since you were last in America?” A note of challenge from the World: it is not good form to live outside God’s own country. “I left in the year 1837. That was the year that everyone went bankrupt. Now I am back and everyone has again gone bankrupt. There is a certain symmetry, don’t you think?

This went down well enough. But wh

y had I left?

“Because I had been appointed American vice consul at Antwerp. By President Van Buren.”

I thought that this would sound impressive, but it provoked no response. I am not sure which unfamiliar phrase puzzled them more: “vice consul” or “President Van Buren.” But then Americans have always lived entirely in the present, and this generation is no different from mine except that now there is more of a past for them to ignore.

Our republic (soon to be in its centennial year) was in its vivacious sixties when I left, the same age that I am now.

Although my life has spanned nearly two-thirds the life of the United States, it seems but a moment in time. Equally curious is Emma’s first impression of New York: “How old it looks,” she said. Yet there is hardly a building left from my youth. As I spoke to the press I did finally recognize through the window—porthole—the familiar spire of Trinity Church. At least no new fire has managed to destroy that relic of the original city.

(Noted later: my “familiar spire,” according to John Day Apgar was torn down in ’39. The current unfamiliar spire dates from the early forties.)

Questions came quickly. My answers were as sharp as I could make them, considering how tactful, even apologetic one must be for having stayed away so long. And if the newspaper reports of my return prove to be amiable, I will find it easy—I pray—to acquire a lecture agent, not to mention magazine commissions from—from anyone who will pay!

“Where have you been living, sir?”

“For the last few years in Paris. I came there—”

“Were you in Paris during the war, during the German occupation?”

I restrained myself; was modest; agréable. “Why, yes, in fact I wrote a little book about my experiences. Perhaps you know the title. Paris Under the Commune?”

The Golden Age: A Novel

The Golden Age: A Novel Death Before Bedtime

Death Before Bedtime Burr

Burr The Last Empire

The Last Empire Empire: A Novel

Empire: A Novel The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal

The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal Live From Golgotha

Live From Golgotha Lincoln

Lincoln Death Likes It Hot

Death Likes It Hot Thieves Fall Out (Hard Case Crime)

Thieves Fall Out (Hard Case Crime) Point to Point Navigation

Point to Point Navigation Williwaw

Williwaw Death in the Fifth Position

Death in the Fifth Position In a Yellow Wood

In a Yellow Wood Julian

Julian Hollywood

Hollywood Myra Breckinridge

Myra Breckinridge Messiah

Messiah The Second American Revolution and Other Essays 1976--1982

The Second American Revolution and Other Essays 1976--1982 Homage to Daniel Shays

Homage to Daniel Shays Empire

Empire Thieves Fall Out

Thieves Fall Out 1876

1876 The City and the Pillar

The City and the Pillar The Golden Age

The Golden Age At Home

At Home